If I have seen further, it is by standing on the shoulders of giants.

– Sir Isaac Newton

The land is process

Our imprint too!

We live in the lee

Of what our forefathers do

– From “Dancing on the Brink of the World – Volume V: Heritage”

Many of us owe a professional debt of gratitude to those who walked before us, people who blazed a trail as innovative giants in an age before our own. In the heritage landscape that is Cypress Lawn Memorial Park, the giants stand on their own, the wooden behemoths of our living collection grown over the course of many decades to define the singular place we now call the Arboretum.

It is their planters, though, upon whose shoulders I stand today; the founders and park stewards of days gone by who cared for the cypresses of Cypress Lawn long before my own era as an arboricultural caregiver.

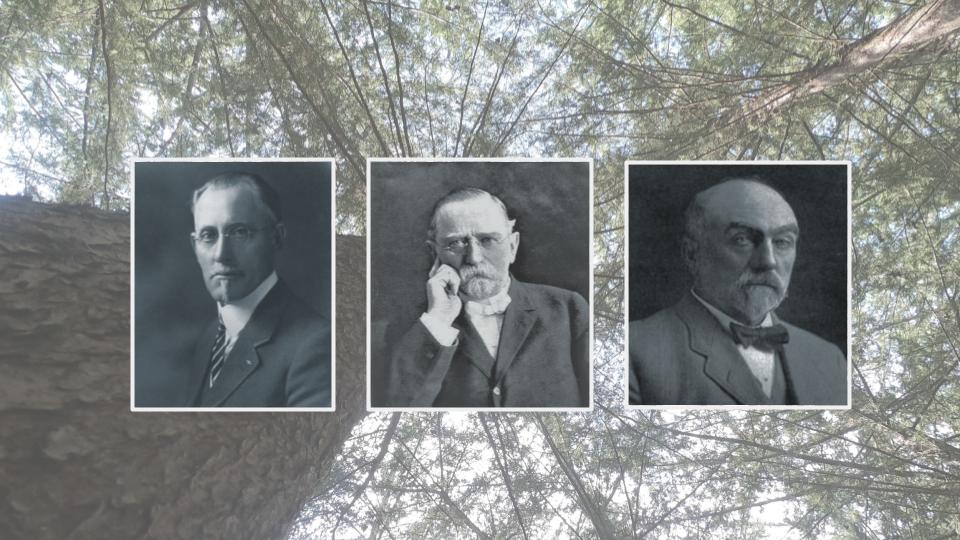

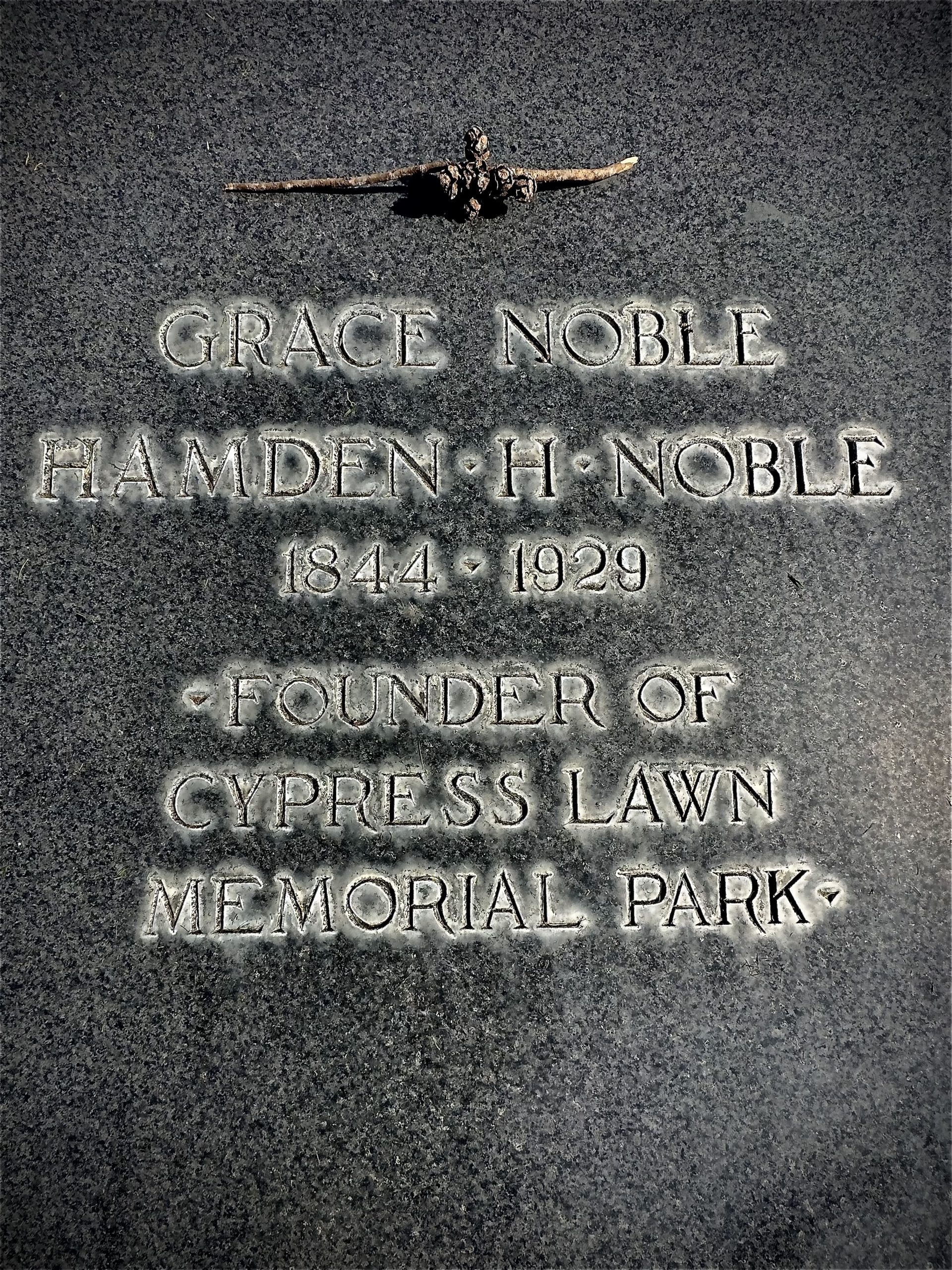

The inheritance of these trees — these majestic living assets! — is a gift I treasure each day walking among our collection, and in the following words I pay homage to the true Fathers of the Arboretum, in whose lee I grow — our founder, Hamden Holmes Noble; the first mayor of Colma, Mattrup Jensen; and a humble decedent of our West Campus, longtime superintendent of Golden Gate Park, John McLaren.

NOBLE

It is simple to say that, were it not for the grand vision of Mr. Noble, I would not have the life I do and the privilege of purpose to care for the trees of Cypress Lawn Arboretum. Hamden Holmes Noble was born on Aug. 16, 1844, the son of a farmer, James W. Noble, in rural Maine. A Civil War veteran, Noble migrated west to California in the 1860s and became a successful entrepreneur and businessman in the mining industry as a member of the San Francisco Mining Exchange. Noble’s burgeoning wealth gave him the opportunity to capitalize upon an important idea, which came to him on a carriage ride one day in the heart of San Francisco.

It is simple to say that, were it not for the grand vision of Mr. Noble, I would not have the life I do and the privilege of purpose to care for the trees of Cypress Lawn Arboretum. Hamden Holmes Noble was born on Aug. 16, 1844, the son of a farmer, James W. Noble, in rural Maine. A Civil War veteran, Noble migrated west to California in the 1860s and became a successful entrepreneur and businessman in the mining industry as a member of the San Francisco Mining Exchange. Noble’s burgeoning wealth gave him the opportunity to capitalize upon an important idea, which came to him on a carriage ride one day in the heart of San Francisco.

The story goes that Noble was passing by one of the original cemeteries of Western pioneers in the aftermath of the Gold Rush, Laurel Hill Cemetery, and was conversing with a friend about the character of the memorial park. At the time, in the late 1800s, San Francisco’s population was exploding, and an era of immense wealth and development was creating a serious land use conflict with original city cemeteries such as Laurel Hill. Noble and his carriage companion recognized this obstacle as a real opportunity for establishing new cemeteries outside of the city limits. Before too long, the area now known as Colma was identified as a suitable place for memorial parks to be developed, and Noble’s visionary ambition led to the founding of Cypress Lawn in the year 1892. It should be noted that the many thousands of decedents originally laid to rest at Laurel Hill reside today at a special group monument of Cypress Lawn’s West Campus, a place known as Laurel Mound, which features a giant obelisk sculpture and an equally massive Monterey pine tree.

Akin to the great landscape architect of New York’s Central Park, Frederick Law Olmsted, Mr. Noble visited precedent landscapes to find inspiration in the planning of his own park. Olmsted’s experiences traveling through the countryside of England formulated his intentions of the rural garden parks that fostered a “genius of place” in the northeastern United States in the 19th century. So too did Noble witness the genius loci of his predecessors, deriving inspiration from the famed Mount Auburn Cemetery of Cambridge, Massachusetts, which was founded in 1831 and itself inspired by the garden cemetery aesthetic of places like Père Lachaise Cemetery in Paris.

In all truth, from its inception, Noble made Cypress Lawn as an Arboretum, in spirit if not in name. In the first decades of stewardship of his new memorial park on the peninsula, trees were planted from all around the world — from Europe, Asia, South America, Australia, New Zealand, northern Africa, and from across North America too. Of course, no species was more prevalently planted at Noble’s park than its California native namesake, the Monterey cypress. These foundational plantings came to define the place I now know and love, and Noble is to thank for much of this intention. One hundred and thirty years later, a noble thought on a carriage ride has become something grand, something deeply rooted in the hearts of many. That thought has become an arboretum.

——————————————–

JENSEN

I hope that man may someday be

As noble as a living tree

Excerpt from the poem “A Tree” by Mattrup Jensen (1931)

Born in Denmark in 1873, Mattrup Jensen moved with his family to the United States as a young boy, eventually settling permanently on the San Francisco Peninsula with his wife, Stella, and their children in 1903. Known as the “Father of Colma,” Jensen played a formative role in establishing our township in the 1920s, protecting our cemetery city through incorporation with the original name of Lawndale. Jensen was the long-serving mayor of Colma for multiple terms in his lifetime and guided this singular “necropolis” as an open space of stone and trees and the everlasting celebration of life.

Uniquely, Jensen actually served as cemetery superintendent for both Cypress Lawn and Olivet, as he was first hired by Hamden Noble at the former property in 1902, and then migrated over to his long-tenured role at Olivet (originally Mount Olivet) two years later. In his brief time at Cypress Lawn, Jensen was responsible for the engineering of our 1.5-million-gallon reservoir, which now defines the entry area south of Cypress Avenue on our foundational East Campus.

Jensen’s mark upon the landscape is far greater than this one project, as he served for 42 years as the primary caretaker of what now lives on as our Olivet Gardens campus. As a cemeterian, it is worth noting Jensen’s immense contribution to his profession in the United States with the invention of the modern crematory retort in the year 1912. Jensen was a renaissance man of his era, making meaningful impacts on the township of Colma as an engineer, a landscape architect, a local government serviceman, and of course, as a steward of trees.

Jensen describes his own relationship to the landscape and plants of Olivet in the following excerpt from his autobiography, published in 1956 one year before his passing:

I have been instrumental in making one spot on this old world, a little more beautiful than I found it. I have always been a lover of the great outdoors. Even as a boy, I was a student of nature. I have also devoted many hours to the growing and planting of trees and shrubs … Some of my happiest hours have been devoted to this type of work.

Jensen was a self-professed lover of trees, an arborist before such a professional title existed, and it was his stewardship and cultivation of the vast collection of century-old Monterey cypresses and pines that define the grounds of Olivet today, for which I owe an interminable debt of gratitude. There is a large specimen of Hesperocyparis macrocarpa perhaps 30 paces away from his grave, a family monument located along the western edge of this historic cemetery originally founded in 1895. The cypress nearby is perhaps the finest singular tree found in the entirety of the Olivet landscape, a gargantuan green being with a crown denser than any neighbor, a branching structure almost entirely devoid of failures, and a trunk wider around than any other specimen in the section. Perhaps, one day soon, we will honor Mr. Jensen’s living legacy by cultivating a seedling of direct offspring from this tree and plant it in the lee of the headstone of the Father of Colma to grace him with its gentle shade for decades to come.

This memorial tree planting idea is just a thought, for now, but Jensen spoke majestically of his belief in the power of thoughts, in his poem of the same name, composed in 1950 and excerpted below:

This memorial tree planting idea is just a thought, for now, but Jensen spoke majestically of his belief in the power of thoughts, in his poem of the same name, composed in 1950 and excerpted below:

Thoughts are but human seeds

Which we may keep or sow,

If planted in some fertile soil

Perchance — they’ll grow

And if they grow, with proper care

They may become so great

That millions of our fellowmen

May share their future state

The life’s work of Mr. Jensen is an extension of his own thoughts, as noble as they were. In growing upon the vision of the Father of Colma, it may just be that our thoughts today, and the cypress trees we plant tomorrow, may grow to be so great that their future state might be shared by many yet to visit our cherished Memorial Park.

The following composition of Jensen himself, one final poem that I would like to share with you, was written about his beloved Olivet, speaking to the glorious sunset hour that falls upon the tree-dotted lawns of this historic cemetery, and the headstone of its foremost steward, on each sunny evening in the town he founded.

Olivet Memorial Park (written June 1, 1911):

“Park Olivet”, thou place of rest

At ev’en tide, I love Thee best

When shadows lengthen o’er Thy green

And all is still, and all serene

When gold and purple hues do rise

Upon Thy hills, and to the skies,

To mingle with the clouds again;

Keep Thou my dust, in safety then.

————————————————-

MCLAREN

A good friend of Mr. Jensen, and I suspect at least an acquaintance of Mr. Noble too, was a man for whom the San Francisco city policy of forced retirement at the age of 70 was suspended, so he could be given a lifetime appointment as the Superintendent of Parks, a position he held for over four decades until his passing in 1943. That man was John McLaren.

A good friend of Mr. Jensen, and I suspect at least an acquaintance of Mr. Noble too, was a man for whom the San Francisco city policy of forced retirement at the age of 70 was suspended, so he could be given a lifetime appointment as the Superintendent of Parks, a position he held for over four decades until his passing in 1943. That man was John McLaren.

The purported planter of over 2 million trees in his lifetime, Mr. McLaren was a Scotsman born at Bannockburn near Stirling in 1846 – the very same year that German botanist Karl Theodor Hartweg began his exploration of the California coast, a journey on which he collected the very first seeds of Monterey cypress known to western science. McLaren studied horticulture in the immersive learning environment of Edinburgh Royal Botanical Gardens before emigrating to the United States as a young man in 1870. In his early years in California, McLaren cared for the estate landscape of Leland Stanford in Palo Alto and also planted many trees at Coyote Point along the bay’s edge in modern-day San Mateo.

Some years later, McLaren’s reputation as a horticulturist and tree steward led to him becoming the chosen successor of Golden Gate Park’s inaugural Superintendent and designer, William Hammond Hall. McLaren and Frederick Law Olmsted were both asked to assess Hall’s tree plantations in the newly established Golden Gate Park in the late 1880s, which was, of course, dotted with hundreds of Monterey cypress seedlings.

This species is uniquely capable among California natives of growing roots into pure sand, which was the native soil type of the dunescape of early San Francisco. The planting efforts of Hall and McLaren, specifically with Hesperocyparis macrocarpa (then known as Cupressus macrocarpa) in the largest park of modern-day San Francisco, were formative in defining the open space aesthetic of the city by the bay.

McLaren also had a living connection to Colma, just a few miles south down the peninsula in the epicenter of California’s memorial parks. For the San Francisco Panama-Pacific International Exhibition in 1915, McLaren and his friend Mattrup Jensen worked together to provide 500 mammoth hydrangea plants as a botanical spectacle for the event. These plants were cultivated on the grounds of Olivet, in the lee of well-established Monterey cypresses. I wonder with all my heart how many of these trees McLaren and Jensen planted together.

There is one special cypress that McLaren definitely planted himself, circa 1880, just outside on the lawn of where his longtime home, now known as McLaren Lodge, was later built in 1896. Fondly referred to as “Uncle John’s Tree,” this 143-year-old specimen has been adorned with lights as the official San Francisco city holiday tree each December since 1929. The lighting ceremonies take place annually on December 20th, in honor of McLaren’s birthday.

This one old specimen gets more care and regular maintenance than many other cypresses from the era of Hall and McLaren that still stand in Golden Gate Park, but even so, a thoughtful contingency plan has been managed in the event of “Uncle John’s Tree” failing someday. A companion cypress was planted 35 yards west of the original in the 1980s and has now emerged into healthy maturity itself. The living legacy of McLaren and his cypresses is in good care, and ever branching out.

This one old specimen gets more care and regular maintenance than many other cypresses from the era of Hall and McLaren that still stand in Golden Gate Park, but even so, a thoughtful contingency plan has been managed in the event of “Uncle John’s Tree” failing someday. A companion cypress was planted 35 yards west of the original in the 1980s and has now emerged into healthy maturity itself. The living legacy of McLaren and his cypresses is in good care, and ever branching out.

McLaren was known as a quiet man, perhaps curmudgeonly at times, and notedly objected to the installation of statuary in Golden Gate Park throughout his tenure as Superintendent. These “stookies” as he referred to sculptures, were not a part of McLaren’s natural vision for the park, and he repeatedly declined to have a statue of himself created to adorn the landscape. In his waning years, McLaren finally relented, and a subtle bronze sculpture of this man of trees, holding a pine cone in everlasting curiosity, now stands in the John McLaren Memorial Rhododendron Dell. A stand of old cypress trees lines the horizon in the distance beyond him.

An even subtler granite monument, of Mr. McLaren’s own choosing, sits today on the West Campus of Cypress Lawn Memorial Park, just a short walk away from the equally modest graves of Mr. Jensen at Olivet Gardens and Mr. Noble on the East Campus. It makes so much sense to me that these giants of their time — planters and stewards of so many magnificent cypress trees — did not feel the need to leave their mark and names in ornate stonework above their bones. Their legacy is alive today, perhaps more than ever, in a place of gigantic vision known simply as Cypress Lawn Arboretum.