By Richard Burrill

April 8, 2022

Please know that Cypress Lawn has recently acquired Olivet Memorial Park in Colma. Situated at the base of the San Bruno Mountains, with huge cypress and palm trees throughout, Mount Olivet — as it was originally named — opened in 1896, four years after Cypress Lawn. Known as the “Cemetery of All Faiths,” it is located at 1601 Hillside Blvd., adjacent to our Hillside Campus.

So, we are now named Cypress Lawn, but the rich history involving Olivet Memorial Park in Colma, is not going away.

Provided below is this blog by Richard Burrill, written on April 8, 2022, for this website.

Richard’s latest work on Ishi is Ishi’s Return Home (2014). He authored Ishi Rediscovered in 2001, which went through five reprintings. His website is: www.ishifacts.com. His current Ishi manuscript in progress covers Ishi’s time in San Francisco, 1911-1916. Look for a pre-publication notice in 2023 or 2024.

In July 2021, I was very surprised to discover that “cancel culture” activists on the UC Berkeley campus, back on July 1, 2020, had temporarily “unnamed” Kroeber Hall to a lesser name in 2020. It is now named, “The Anthropology and Art Practice Museum.”

I am concerned about Professor Alfred L. Kroeber’s legacy fading away from our next generation, the hope for the future. I discovered from my comprehensive research that a mutual and genuine friendship between Ishi and Kroeber remained long-lasting.

Please be sure to understand, contrary to what a few individuals are circulating, “ALFRED KROEBER DID NOT ORDER AN AUTOPSY OF ISHI, when Ishi died from tuberculosis in San Francisco on March 25, 1916.”

Figure 1: Kroeber and Ishi in September 1911.

Photo: Louis Stellmann.

So, to help correct matters, I present in 12 pages (word count 3,369) this essay with some “Truthful facts of Ishi and Alfred Kroeber’s friendship.”

I encourage the reader to read these facts and then decide for yourselves whether an injustice has been done to Professor Alfred L. Kroeber, who was born in 1876 and died in 1960. Indeed, it was in 1960, in the twilight of his life, when Kroeber learned that the newly built anthropology department building, with the Robert Lowie Museum of Anthropology adjoining it, was renamed Kroeber Hall, in his honor.

News update: Then in 1992, said Lowie Museum of Anthropology was declared (renamed) the Phoebe A. Museum of Anthropology because it celebrates the fact that 1992 marked the ninth decade of existence since the museum was founded by Phoebe A. Hearst in 1901.

* * * * *

At Colma, Ishi’s remains were cremated on March 27, 1916, and on March 31, Ishi’s remains were placed in a jar and placed in the columbarium there. Fast forward some 84 years to 2000. According to Orin Starn’s Ishi’s Brain (2004:262) the unnamed superintendent of Olivet Memorial Park cemetery “had no objection to giving up Ishi’s ashes” to the designated Native representatives of the Redding Rancheria and Pit River tribes who were designated by the Smithsonian Institution to receive Ishi’s brain, that on August 9-10th, 2000, was buried in a discreet place in the Ishi’s Wilderness.

But this much is not the end of the story. Rather, it is in a real sense, only the beginning.

Ishi was a resident in San Francisco, from 1911 to 1916. In 1911, an unarmed and hungry Native American was chased up a black oak tree by four barking cattle dogs on the Charles Ward Slaughterhouse grounds near downtown Oroville.

In short order, three butchers ran up to the “closing pen” corral and witnessed the dark-skinned intruder in the tree, with the dogs below threatening him. They shooed off the dogs. Seeing the situation now safer, the stranger stepped down from the oak, scaled down the high fence, and dropped to the ground, prepared for what fate would bring him.

Next, a fourth butcher named “Ad” Kessler, age 19, came running up. With a metal hog gambrel club held up in one strong hand, he grabbed the man by the shoulder, forcing him down. In no manner did he resist the rough treatment, so he dropped this lethal weapon. The man was barefoot with soles that were calloused like leather. Through the septum of his nose, he wore a small labret of wood the size of a matchstick. Kessler bit his lip. He judged he was not a “Mexican” at all, but rather a real, wild Indian!

Figure 2. First photo in San Francisco newspaper that made the mysterious Indian a national sensation. “The Call” Aug. 31, 1911, John H. Hogan photo.

Authorities took the aboriginal man into custody for his own protection. He was taken to the Butte County Jail.

News of the so-called “Last Survivor of Stone Age California” was a sensational story that attracted national attention. The stranger’s given name became “Ishi, which means “man” in his Yahi language. Ishi’s time in San Francisco, as a remarkable and colorful resident, was 1911 to 1916.

This man would prove to be the last member of the Yahi tribe who hid in the Deer Creek and Mill Creek drainages of northern California. He never did divulge his tribal family name, in accordance with the old Yahi tradition of not revealing personal identities to outsiders or enemies.

The Yahi were hunter-gatherers and horticulturalists. The nation of some 400 remained isolated from the outside world for 22 years longer than Geronimo’s band of Apaches. Fortunate for the Yahi, Ishi’s Deer Creek had virtually no gold ore that the 49ers would have exploited to the maximum like they did at Coloma. By 1865, the approximate 18 remaining members of the tribe hid in the foothills. They were thought to be extinct until that fateful day in 1911 when the one of them unexpectedly appeared in Oroville.

Anthropologist Thomas Waterman at the University of California, Berkeley, gathered up what partial vocabulary list his department had of Northern Yana words and traveled to Oroville. On September 1, in the night, Waterman visited the prisoner and succeeded at communicating in a crude exchange over the word si’-win’i for “yellow pine” as opposed to iwi, the word for simply “wood.” His face beamed in excitement.

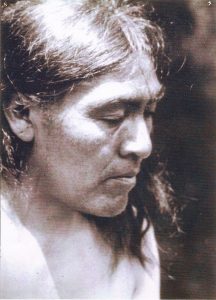

Figure 3. A. L. Kroeber 1914 photo of Ishi on Deer Creek, 15-5725, of face only.

All American Indians at the time, under the law, were “wards” of the U.S. Secretary of the Interior’s Bureau of Indian Affairs, who routinely kept Indians on reservations because, “that was simply where Indians belonged.” U.S. stewardship over Indians remained in place until the Snyder Indian Citizenship Act was passed by Congress in 1924. No reservation had been established specifically for Yana-Yahi Indians.

Anthropologist Alfred Kroeber successfully negotiated permission for Ishi to remain at the University to primarily study Ishi’s language, while his final disposition was being finalized. On about December 13, 1911, Ishi stood before Special Agent Charles Kelsey at the Museum in San Francisco. According to author Theodora Kroeber (1961:218) of Ishi In Two Worlds, Ishi gave a prompt and unequivocal response, answering Kelsey in Yahi:

“I will live like the call-tu [“white man”} for the remainder of my days. I wish to stay here where I now am. I will grow old in this house, and it is here where I will die.”

The Bureau of Indian Affairs respected Ishi’s wish for the time being.

Time passed. By the end of 1913, it was observed that Ishi was beginning to speak words and phrases of American English. Ishi remained content living in the corner room with bed and kitchenet that Kroeber established, reserved for “visiting scholars.” Kroeber also convinced the Regents of the University to retain Ishi on the payroll as a Museum staff member. One of his unique assignments that Ishi excelled at was teaching on most every Sunday, from 1 to 4 p.m. He was a teacher of California Indian traditional skills, most popular being flint knapping, traditional fire-making, and by 1914, demonstrating his skill with bow and arrows.

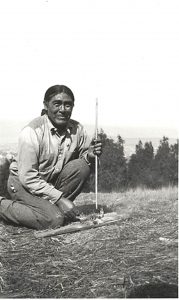

Figure 4. Saxton Pope photo (15-6277) of Ishi at Mount Sutro overlook, circa 1913 probably.

The last time the B.I.A reviewed Ishi’s case was October 16, 1914. Assistant Commissioner of Indian Affairs, E. B. Merit’s letter announced that there was “no need to interfere with Ishi’s living and work conditions.” Not until August 22, 1915, did Ishi’s latent tuberculosis abruptly change to the tuberculosis disease that required hospitalization because now, he was contagious to others.

Well before Ishi’s death, the University anthropology professors Alfred Kroeber and Thomas Waterman and Edward Gifford, Museum Assistant Curator, had all learned from Ishi that his Yahi culture believed that the body after death must never be desecrated. Also, during Ishi’s return home expedition in 1914, Kroeber had visited #24 Wa’laptina (“Ancestor’s Cave”) that was likely a cremation site for the dead. Kroeber (1925:341) would write in his Handbook of the Indians of California, that whereas “The two northern divisions buried the dead, the Yahi cremate.”

So even before Alfred Kroeber departed UC Berkeley on June 1, 1915, for his one-year sabbatical to the American SW, New York, Europe, Washington D.C., and back to Zuni territory in the SW, Kroeber made it known to all that if and when Ishi died, that their friend Ishi was entitled to a traditional Yahi cremation, and nothing else would do.

Figure 5. Ishi’s first full day in San Francisco, Sept. 5, 1911 (15-5401).

Ishi’s Decline

It would be on November 21, 1915, when Professor Alfred Kroeber arrived states-side in New York, just back from Europe. It was then that Kroeber learned from Western Union telegrams and Thomas Waterman’s November 7th letter that Ishi was very ill in San Francisco and that he would die soon from tuberculosis.

Waterman said that Ishi had been kept in the hospital until early October 1915, when, as he put it, “they could not accommodate him further. Then at museum staff member Arthur Warburton’s suggestion [on about September 30], we rigged up the Pacific Islands room for an infirmary and put him in there. Warburton is taking fine care of him and [Saxton] Pope says he is better off than in the hospital” (Kroeber Papers).

What to do? The first six months of Kroeber’s year-long sabbatical was over. He was in New York. Kroeber’s expansive manuscript with working title, Handbook of Indians of California, he felt so compelled to finish writing in New York before his academic leave ended. Kroeber did keep steady and caring correspondence via telegraph, telephone long-distance, and writing anecdotal correspondence directed for Ishi to hear.

Figure 6. Nels Nelson photo of Ishi (15-5423). Ishi sits at Yana house he built in March 1912.

Kroeber valued and received some solace from the fact that Dr. Saxton Pope was Ishi’s primary care physician. “Pope has the only right idea, which is to handle him as a person, not as a hospital case” (Kroeber letter to T. T. Waterman Aug. 28, 1915).

Kroeber trusted that Dr. Pope would support Ishi’s wish that a traditional cremation was in order for Ishi when the inevitable end came. Upon death, Pope would surely not desecrate Ishi’s physical remains. No autopsy, no embalming at any undertaker’s; only cremation was the Yahi way.

Days and then weeks passed, and when Edward Gifford’s February 4, 1916, letter to Kroeber arrived in New York was “the capstone” or last window of opportunity to return to San Francisco “to see Ishi before he died,” explained editor and historian, Grace Buzaljko ( 2003:54). Gifford’s letter read:

“Dr. Pope . . . says his condition is not at all reassuring . . . . Pope believes that the disease is spreading to the stomach and intestines, and furthermore, that Ishi is gradually failing” (Kroeber Papers).

It was the next correspondence to New York received, and dated March 18, 1916, from Edward Gifford, that told Kroeber that Ishi’s death was impending:

“Yesterday, Doctors Summersgil and [illegible?] visited Ishi. For the first time his sputum shows signs of tubercolsis [sic] germs. Pope came in this morning and removed Ishi to the isolation ward in the hospital . . . Pope says he will probably not last over two weeks, or a month at the outside. He [Pope] wants to make a cast of his face and hands after death; also to perform an autopsy. I told him that it is your order, and the Indian’s wish that he have a proper burial . . . .

“Although Pope did not say so, I gathered . . . that the hospital would like to have the body. I am going to see Waterman immediately” (Buzaljko 2003:54).

Lastly, Gifford added, “Upon receipt of this letter, if you have any further instructions, you had better telegraph them (Gifford-Kroeber Letters).”

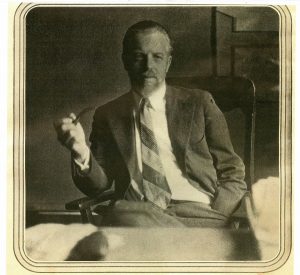

Figure 7. Photo of Alfred L. Kroeber in 1911. Photographer unknown.

Career editor and unofficial historian of the Anthropology Department of the University of California, Berkeley campus, Ms. Grace Buzaljko (2003:55) explained how Kroeber responded immediately. Alfred Kroeber’s entire letter of March 24, 1916, is reprinted below (reprinted from Robert Heizer and Theodora Kroeber, eds.(1979:240) reads:

Dear Gifford,

I am very sorry. The temperatures made me lose hope some time ago.

Please stand by our contingently made outline of action, and insist on it as my personal wish. There is no objection to a cast. I do not however see that an autopsy would lead to anything of consequence. I might be willing to consent if it were to be a strict autopsy in the ordinary sense to determine the cause of death, but as they know that, I suspect that the autopsy would resolve itself into a general dissection. Please shut down on it. As to disposal of the body, I must ask you as my personal representative on the spot in this matter, to yield nothing at all under any circumstances. If there is any talk of the interests of science, say for me that science can go to hell. We propose to stand by our friends.

Besides, I cannot believe that any scientific value is materially involved. We have hundreds of Indian skeletons that nobody ever comes near to study. The prime interest in this case would be of a morbid romantic nature.

Please acquaint Waterman with my feelings, and convey them also to Pope, toned down in form so as not to offend him, but without concessions.

When the time comes, please see that the various people in the hospital are properly thanked. They have been more than white.

You can get an individual plot in any of the public cemeteries. Draw upon any money in our keeping, for this purpose without question or formality, on my responsibility. As to monument and care, we can see later. There is no use declaring an estate unless there is official demand. Whatever balance remains after we get through, I think should be turned over to the hospital for what they have done. All this, however, can be arranged later.

Yours,

A. L. Kroeber

Grace Buzaljko (2003:55) wrote:

The letter arrived too late. The telegram was received at Western Union in downtown San Francisco at 6:17 a.m. on March 25. Ishi died that day at about 12:00 noon that day.

Events Upon Ishi’s Death

March 25 — Ishi died at 12 noon. “The autopsy was performed [at the UC Hospital] a few hours after the death of Ishi by Dr. Jean V. Cooke” (Pope 1920:209, 212). A new actor in this drama is introduced. Brain – Weighs 1,300 grams. It is removed.

March 27, 1916 — Dr. Saxton T. Pope Sr. (1920:213) wrote:

His body was carried to the undertakers, where it was embalmed. No funeral service services were held. Professor T. T. Waterman, Mr. E. W. Gifford, Mr. A. Warburton, Mr. L. L. Loud, of the Museum of Anthropology, and I visited the parlor, and reverently placed in his coffin his bow, a quiver full of arrows, ten pieces of dentalia or Indian money, some dried venison, some acorn meal, his fire sticks, and a small quantity of tobacco.

We then accompanied the body to Laurel Hill Cemetery [Mount Olivet] near San Francisco, where it was cremated. The ashes were placed in a small Indian pottery jar on the outside of which is inscribed: “Ishi, the last Yahi Indian, died March 25, 1916.”

Two more attendees who joined the aforementioned were “John Alden Mason of the Philadelphia Museum and Alfred Lee Loomis of the Academy of Sciences” (T. Kroeber 1961:236).

March 27, 1916 — Cremation date. Mount Olivet files contain a receipt dated March 27, 1916, c/o public administrator for $40 and an internment document describing name, date of death, approx. age, color, sex, and place of birth.

March 31, 1916 — Ishi’s ashes were placed in a Pueblo jar and placed in the columbarium of Laurel Hill / Mount Olivet Cemetery.

Figure 8. “ISHI, THE LAST YAHI INDIAN, 1916,” inscription on black serpentine urn, containing Ishi’s ashes at Olivet Cemetery, Colma, CA. Author’s photo, Dec. 26,1997.

Figure 9. Author in 1997, stands in front of Olivet Columbarium wherein Ishi’s ashes were preserved at that time.

Events After Alfred Kroeber Returned

Late August, 1916 — Alfred Kroeber returned from Zuni to the Museum in San Francisco. He unlocked the door to his office and walked in. On his desk he discovered a wet jar with a human brain. Presumably upon reading its packing label, Kroeber discovered it was, horror of horrors, Ishi’s brain. Kroeber became distraught. Surely, he wondered who sent him the brain? Pope? Later Cooke’s name must have come up for Kroeber.

Kroeber felt dumbfounded, for it took Kroeber two months before he acted. We come to October 27, when Kroeber contacted Curator Aleš Hrdlička at the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C., who had the world’s largest primate brain collection.

“I find that at Ishi’s death last spring his brain was removed and preserved. There is no one here who can put it to scientific use. If you wish it, I shall be glad to deposit it in the National Museum collection.”

This act by Kroeber when distraught and under duress, when he wrote, asking would the Smithsonian accept Ishi’s brain for their collection, became a hard fall by Kroeber for many to accept. Former “chair” of Anthropology at Berkeley, George M. Foster, admitted “By sending Ishi’s brain to the Smithsonian, Kroeber violated a sacred trust with Ishi (K and K 2003:93).”

Figure 10. Photograph of Professor Alfred L. Kroeber taken circa 1928. He was the first anthropologist at UC Berkeley, beginning in 1901.

But Emeritus Professor George Foster (2003:98) in his same essay titled “Assuming Responsibility for Ishi” also speaks for their being a moral compass that avowed “Kroeber critics” may do well to consider. Foster explained:

“Everyone has a right to expect from history that its judgments be made against a background of total performance, not on the basis of a single episode, evaluated by the standards of a later point in time.”

What the above history with letters written from the heart by Alfred Kroeber reveals, is that Kroeber cared dearly about Ishi as his friend. We learn that Ishi being autopsied at death was the last thing Kroeber would have ever permitted because he knew Ishi’s belief system. Also, if and when any hospital patient died in a University of California Medical Teaching Hospital, an autopsy was standard practice and done without exceptions.

In 1999, Duke University Professor Orin Starn, while studying in the Bancroft Library, chanced upon Kroeber’s 1916-1917 letters to Aleš Hrdlicka at the Smithsonian, asking if he would accept Ishi’s brain. Starn’s discovery and walk alongside determined California Indians led to the W. W. Norton publication Ishi’s Brain (2004). In 2000, California Attorney General Bill Lockyer and the California Native American Heritage Commission filed suit in San Mateo Superior Court to allow Ishi’s created remains to be removed from Olivet Cemetery, in Colma. Because the Smithsonian decided that Ishi’s closest cultural affiliations were the Native people at Redding Rancheria and Pit River tribe, the respective representatives received Ishi’s brain. Today Ishi’s remains rest in a secret location in the Ishi Wilderness, guarded from curious seekers.

Figure 11. Ishi story author Richard Burrill stands in the foreground on the University of California, Berkeley campus. Photo taken on March 23, 2022.

Richard Burrill: “Thank you for taking the time to read my blog titled, “The Truthful Facts of Ishi and Alfred L. Kroeber’s Friendship.” Behind my left shoulder (above) is the Anthropology Department building that in 1960 was completed and in 1960, named Kroeber Hall in honor of Alfred L. Kroeber’s lifelong contributions for perpetuity which normally means “forever.” This world scholar died only about three months later. But sixty years later, in the middle of the COVID-19 pandemic, in July 2020, Kroeber Hall was temporarily unnamed. Now, this landmark building is called the non-descript name, The Anthropology and Art Practice Museum.

The other structure behind me, to my right, back in 1960 was the Robert Lowie Museum of Anthropology. Since 1992, however, a second name change took place regarding it. The Lowie Museum of Anthropology was re-named the Phoebe A. Hearst Museum of Anthropology, to celebrate nine decades of existence since the Museum of Anthropology was founded in 1901 by widow and philanthropist Mrs. Phoebe A, Hearst.

Updates And New Name Proposals Are Welcomed. See Notice Link Below.

Yes, the fuss or kerfuffle continues on the UC campus about what will be the future name of unnamed Kroeber Hall. MY SHOUT OUT IS THAT WE RE-CHRISTEN KROEBER HALL, “ISHI- KROEBER HALL” – Richard Burrill

What say you? You can write me at <richardburrill2011@gmail.com> as well as to the link below.

Our voices and comments are still welcomed today by the Building Name Review Committee for the proposal to remove the un-named Kroeber Hall. NOTICE: Said proposal is available at: https://chancellor.berkeley.edu/task-forces/building-name-review-committee/building-name- review-kroeber-hall.

References (of R. Burrill blog, May 4, 2022)

Burrill, Richard. Collection “My Next Best Interview Tape Recordings Of the Expanded Ishi Story” #051 – 100 (1970 – 2015). Chico, California.

_____Ishi’s Untold Story In His First World, Parts I & II.

Red Bluff, California: The Anthro Company, An Imprint of Paragon Publishing, 2011.

______ Ishi’s Untold Story In His First World, Parts III & VI.

Bluff, California: The Anthro Company, An Imprint of Paragon Publishing, 2012.

______ Ishi’s Return Home: The 1914 Anthropological Expedition Story.

Red Bluff, California: The Anthro Company, An Imprint of Paragon Publishing, 2014.

Burrill, Richard (Work in progress) Ishi’s Time In San Francisco, 1911-1916 (Five volmes) Buzaljko, Grace, in Burrill Collection interview April 17, 1998 #077 Side A.

Buzaljko, Grace. “Kroeber, Pope and Ishi” In “Kroeber, Karl and Clifton Kroeber eds. Ishi In Three Centuries. Lincoln, Nebraska: University of Nebraska Press, 2003, pp. 48-64.

Fine, Paul, Chair of Department of Integrative Biology. Unnaming Kroeber Hall Controversy blog on News Berkeley.edu:, retrieved Online April 10, 2021. blog posted at News Berkeley.edu by Prof. Charles Hirschking and Prof. Paul Fine.

Foster, George M., “Assuming responsibility for Ishi An Alternative Interpretation in “Kroeber, Karl and Clifton Kroeber eds. Ishi In Three Centuries. Lincoln, Nebraska: University of Nebraska Press, 2003, pp. 89-98.

Hirschking, Charles. Chair of Department of Anthropology. Unnaming Kroeber Hall Controversy blog posted at News Berkeley.edu:, retrieved Online April 10, 2021.

Heizer, Robert, and Theodora Kroeber. Ishi the last Yahi a Documentary History. Berkeley, California: University of California Press, 1979.

Kroeber, Karl and Clifton Kroeber (editors). Ishi in Three Centuries. Lincoln, Nebraska: University of Nebraska Press, 2003.

Kroeber, Theodora. Ishi In Two Worlds. Berkeley, California: University of California Press, 1961 _____ Alfred Kroeber: A Personal Configuration. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1970.

Scheper-Hughes, Nancy. “Ishi brain Ishi’s ashes: Reflections on anthropology and Genocide” in “Kroeber, Karl and Clifton Kroeber eds. Ishi In Three Centuries. Lincoln, Nebraska: University of Nebraska Press, 2003, pp. 99-131.

_____ “Alfred Kroeber And His Relations With the California Indians” July 24, 2020. Blogs Berkeley.edu.

Starn, Orin. Ishi’s Brain, In Search of America’s Last “Wild” Indian.

New York, New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 2004.