His body is here. His head (skull) sits at the Warren Anatomical Museum in Boston. Phineas Gage is perhaps the most famous neurological patient in modern history, one of the “great medical curiosities of all time” and a “living part of medical folklore.”

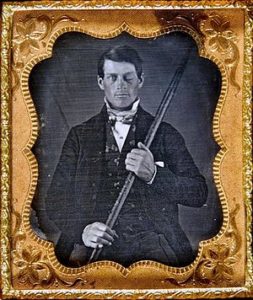

Gage and his constant companion, the inscribed tamping iron sometime after 1849, seen in the portrait which “exploded the common image of Gage as a dirty, disheveled misfit.”

Working as a munitions foreman for a railroad company in September, 1848, the young, robust man was the victim of an accident where a premature exposition cause a 3′ 7″ inch long, 1.4″ in diameter tamping rod weighting over 13 pounds to rocket into the left side of Gage’s face in an upward direction just forward of the angle of the lower jaw. Continuing upward outside the upper jaw and the fracturing the cheekbone, it passed behind the left eye, through the left side of the brain, and out the top of skull through the frontal bone.

Like a pioneer macho man, Gage shrugged off the injury, announced he was not “much hurt” and expected to be back at work in a few days. The attending physician, Dr. Harlow, cleaned up the injury, stopped the hemorrhaging, and wrapped the wound. His recovery from his horrific event was one of top medical stories of the era. Doctors around the world exchanged ideas and theories on the details and implications of the accident. For many years, the incident became the standard against which other injuries to the brain were judged. Some refused to believe that anyone could survive such an ordeal and even suggested that the incident was a fabrication.

Despite his own optimism, Gage’s convalescence was long, difficult, and uneven, which required further work by Dr. Harlow, but by April 1849, the patient was described in good physical health and basically recovered. Gage had, however, lost vision in his left eye, suffered a large scar on the forehead and a deep depression on the top of his head, “beneath which the pulsations of the brain can be perceived,” Doctor Harlow noted. “…Has no pain in head but says it has a queer feeling which he is not able to describe.”

Phrenologists contended that destruction of the mental “organs” of Veneration and Benevolence caused Gage’s behavioral changes. Harlow may have believed that the Organ of Comparison was damaged as well.

Gage continued to work as a long-distance stagecoach driver, owner of stable and coach service, and a farmer, but suffered from occasional spells of seizures and then epilepsy, dying in 1860, twelve years after his injury. There were many reports that he underwent dramatic and negative personality changes – becoming a boastful, brawling, foul-mouthed, dishonest and useless drifter, unable to hold down a job – but these claims are refuted by others and by Gage’s work history. Dr. Harlow asked for and received his patient’s skull. The body was buried in Laurel Hill Cemetery in San Francisco and became part of some 35,000 remains from there that were removed to Cypress Lawn in 1940. Dr. Harlow also received the tamping rod, which Gage carried with him wherever he went, and when given to Harvard was inscribed:

This is the bar that was shot through the head of Mr Phineas P. Gage at Cavendish, Vermont, Sept 14, 1848. He fully recovered from the injury & deposited this bar in the Museum of the Medical College of Harvard University. Phineas P. Gage Lebanon Grafton Cy N–H Jan 6 1850.

Terry Hamburg, Cypress Lawn Heritage Foundation